News & Updates

Poems Lost and Found Along the Trail: Jarod K. Anderson’s Story

In a small white house in Ohio, tucked between a forest and a cemetery, Jarod K. Anderson scribbles out inklings of half-captured inspiration gathered during his morning walk.

Some, like the above, are shared with and loved by wide audiences on Instagram, Twitter, and in bookshops. Others turn into that kind of self-reflective musing that stays beholden only to the author.

Dubbed the Cryptonaturalist (crypto from the Greek root for hidden, not from technology), the poet and podcaster has captured nature-lovers’ hearts and minds, mine included. Formerly entrenched firmly within science fiction, Anderson’s ability to combine that genre’s viewpoint of constant wonder and bewilderment with the natural world is a boon for us all.

While we may all profess to understand a tree as so much more than just a tree, sometimes it takes a wordsmith like Anderson to reawaken that sense of grandiose connectedness and belonging. Anderson well understands the need for this sense – he credits, in part, a strengthened connection with nature these past few years to his successful management of chronic depression.

I wanted to sit down with Anderson to discuss how these works of his come about, about the artist’s relationship with nature, and about how he relates to Leave No Trace principles in his work. I hope you enjoy our conversation and that his words bring you some peace today.

M: Hi Jarod! Thank you again for taking the time to be with us. Do you mind if we start a little off-beat? Rather than introducing us to yourself, could you first introduce us to the nature you’ve been spending time in, that has been inspiring you?

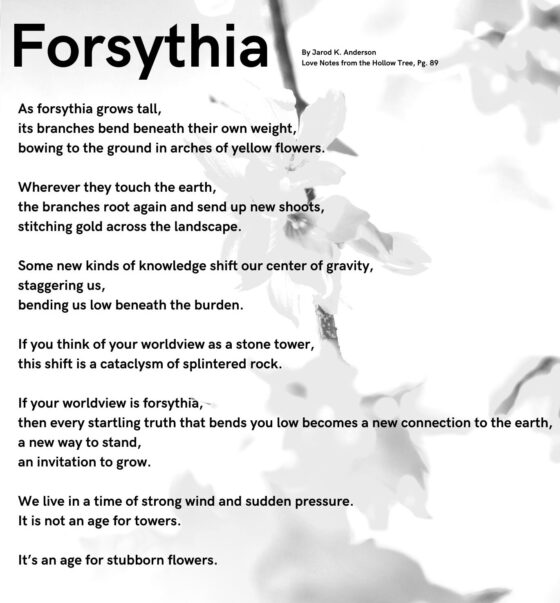

Jarod: Sure! Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time in a little park near my home called Shale Hollow. It’s a 200 acre plot not far from a busy road I often travel. It’s the kind of place where I can spend hours wandering, or I can stop in for a quiet moment and a deep breath.

It has a small, winding stream carving its way through shale formations. Some of the formations are tall and show off round concretions the size of beachballs. Hard, round, compacted stone pressed within the layers of rock. They look a little like marbles tucked into the pages of a book. It’s a good place to watch squirrels or glimpse a blue heron fishing in a shallow pool.

And all those tall formations of thinly layered stone remind me of the power of incremental effort, that most worthy things happen slowly.

M: Sounds like an idyllic spot. What about your background with nature? Where’s that attachment stem from?

Jarod: My background with nature goes as far back as I remember. My family didn’t really have religious affiliations, but my mom would take me on these long nature walks in rural Ohio – she always called it her church. We’d be out in the woods, always discussing what we were seeing.

The next milestone I remember, still young, is being taken outside for class by an elementary teacher who gave us little journals and had us sit down and write about what we saw. She was a poetry lover and so she’s the one that got me started writing poetry.

It was a strange time, though, because I remember writing a poem that won a statewide poetry contest when I was 10 – I had to miss football practice for the banquet… [laughs] it was like, okay, here we go. It was an introduction to the masculinity conversation I’ve been fighting back against ever since.

So yes, time in the woods and time in nature has always felt medicinal to me. In undergrad I was both a biology and English major – English eventually won out, though I don’t think too many literature majors go through zoology for science majors… I got my bachelors in literature at Ohio State, then my Master’s at Ohio University, but stopped short of a PhD.

Being drawn to mission-driven work, I spent some time at Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Columbus, working in fundraising at a beautiful greenhouse. I was helping with their giving database and writing grants. From there, I returned to academia, working at Columbus State Community College, then Ohio University’s Zanesville Campus.

I had a nice career in nonprofits and education. I stepped away from my career, dealing with pretty severe depression, and then I started this strange side podcast, the Cryptonaturalist. [laughs]

M: The Cryptonaturalist is quite fun, but I’m not exactly sure how I would go about explaining it to our audience without them listening. Can you take a stab at it?

Jarod: I like to describe it as real love letters to fictional animals, which really stood in for a metaphor about my relationship with nature. I thought I could let other people access that wonder a little bit by using mythical creatures.

The whole project, it’s funny, it’s fictional, but the motivation behind it was all about honesty – it was “I don’t care if anyone listens to this, what do I want to do?” So it really is about love letters to nature through the lens of speculative fiction.

From there, I just started publishing more and more nature poetry, sharing more online. This all turned into a full-time job of writing and creating! I’m much more the voice of an enthusiast than an expert.

M: And yet I and many experts find comfort in your works. For those less familiar with you, what do you believe drives this comfort people get from your poetry? Do you strive for any kind of overarching themes?

Jarod: I think, sometimes, my work resonates because it rings true. If I talk about how, for example, your body fits into the water cycle – I’m not asking anyone to believe anything that is a stretch. I’m just bringing a different perspective to information they likely already know.

I think it is resonating now because, with quarantine, with what we know about the malicious sides of social media algorithms… there’s a sort of placelessness that happens when you spend so much time online. So, as I’m writing about the physicality of nature, and how we’re linked to that physicality literally and metaphorically, I think it relieves a bit of anxiety about “I have no place in this world.”

I read doom and gloom all day and it sometimes feels like too much, especially in light of my struggles with mental illness. So taking a moment and understanding that our selves, our minds, and our bodies are as natural as any wilderness landscape – it helps promote kinship to our environment and a general sense of wellbeing.

And I like the questions that arise from this. What does this kinship mean? How can that kinship motivate us to care for ourselves and others? How can it reframe our place in the world? I’ve found these ponderings have been a huge relief for people – I get messages all the time about readers’ struggles with dread, with eco-anxiety, with their mental health.

So often when I’m writing I’m thinking about those people. They keep me engaged in my work.

M: You mentioned that there’d be a forthcoming book detailing how nature has helped with chronic depression. As someone who also manages mental illness, would you mind if we sneak a peek into that story?

Jarod: Yes, so that’s a project with Timber Press, they’re a cool publisher who have been doing books about gardening and ecological tie-ins since the 70s. They approached me about doing a nonfiction work on nature and mental health. A bit of a dream come true for me.

We’re approaching it as a memoir. I structured the book in four seasons, with each chapter tied to a plant or animal around Ohio that means something to me and I explore parallels between nature and my mental health journey. I’m really enjoying writing this book.

It is mainly written about the period when I chose to leave academia. I was at a real low-point with depression, feeling very suicidal. Everything was hard. Everything.

Figuring out how to seek healing – and why to seek healing – led me to reaching back to those walks with my mother. To when I was spending a lot of time reading and sleeping in a sugar maple tree as a kid. These thoughts helped to recenter me, to shift my mindset from the career-centered me back to that other guy – the old version of me, the one pleasantly lost in the treetops. I thought about what that old version of me deserves and needs. What advice would he give me now?

In the lowest points of depression, for me at least, the last thing I wanted to do was seek out professional help. I was slow to do that, but what I could do was go for walks in the woods.

I am careful not to oversimplify the relationship between nature and mental health. You won’t see me say, “touch a tree and you’ll feel better.” I mean, yes, touch a tree and you may well feel better, but it’s not a cure nor a panacea. I say that time in the woods, for me, turns depression from the pain to a pain. It’s now just something happening in the mosaic of things that are happening, which makes the pain significantly easier to tolerate and allows breathing room for self reflection.

Doing that over and over, connecting with nature and simply going out and being silent, without an identity to perform, that eventually gave me the room and the headspace I needed to go and seek treatment.

M: For those others who are struggling at present, do you have any words of encouragement or advice from a naturalist’s viewpoint – other than going and touching a tree?

Jarod: I wrote a piece about hopelessness the other day, actually. That, like most things I post, is a kernel of an idea that will grow into a more fleshed out poem. Here, let me go find it…

We seldom admit the seductive comfort of hopelessness. It saves us from ambiguity. It has an answer for every question – there’s just no point. Hope, on the other hand, is messy. If it might all work out, then we have things to do. We must weather the possibility of happiness.

My advice is to weather the possibility of happiness.

It can be profoundly difficult to even allow for the possibility of a better future, especially when our brains scream at us to give up. Sometimes the first step is to nurture a little hope.

M: My wife and I were just talking about this on our most recent walk, actually. The lines between actionable hope and embracing uncertainty.

Jarod: Yes, exactly. For me it is less about accepting uncertainty, and more about learning a new relationship with control, or lack thereof. Two sides of the same coin. Making peace with uncertainty. Making peace with what we do not control. Though, that isn’t the same as apathy. There is always something we can control or influence.

I know I still get frustrated with these concepts and that frustration can lead to shame.

So along those same lines, I’d like to also share a completed poem of mine, Shelter, from my new poetry collection Love Notes from the Hollow Tree.

If our brains are as natural as leaves, we can’t really view them as “broken” as easily, can we? That idea is working for me, at least.

M: I love it. That relationship with nature has led to two poetry collections thus far – Field Guide to the Haunted Forest and Love Notes from the Hollow Tree. Zooming back a little bit, I know that your early life relationship with nature was strong, but then dissipated for a time. You were focused more on science fiction. What brought you back to the field (literally and figuratively)?

Jarod: Yeah, it’s interesting, I find the switch to be more a delineation of subject matter, rather than emotion. So, they tend to mingle in my mind. My writing is still more about a sense of overarching wonder about all nature and especially the nature I find close at hand.

I’m trying to capture that sense, even if I’m writing about things that are not literally true. Science fiction and fantasy, both, act like gateways to a feeling – I used to be very obsessed with those genre distinctions, but they’ve gotten blurrier as I’ve gotten older.

Really, the project for me which started with science fiction but is moving to a more science-based approach is getting people to feel that sense of awe I feel about the world in a way they can access every day. A lot of people use the term escapism for science fiction and fantasy – what I’m trying to do is say “you can have that sense and throw the word escape out completely. It’s here. It’s right outside. Go look at it!”

Spend a couple hours learning about fungal networks and tree roots. A couple hours on why we have an oxygen atmosphere. On how iron functions in your blood. On where that iron originated. Any of these things, I think, will tickle that little synapse that we get from reading about magic and elves.

M: I agree wholeheartedly — you’re about the same age range as me, so maybe this anecdote will make sense. As a kid I loved Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. I still, on my walks, will drift into a fantasy about being the size of a small bug – from that angle, grass is an amazing forest!

Jarod: Absolutely. I think even just lying on your stomach can help folks with a new perspective. We grown-ups forget to do that sometimes. I did it the other day, at the edge of a flower bed. If you just lie there, open to your senses, you’re going to see some amazing things you would not have caught while walking around.

Sometimes, yeah, you need to change the scale of what you’re looking at. Zoom in a bit.

M: Leave No Trace as an ethos feels deep-rooted in your works – again, that interconnection between humans and nature. Do you have a particular affinity towards any of the 7 Principles?

Jarod: All of them are easy to agree with, but for this conversation I wanted to lean towards the sixth, respecting wildlife. I typically go into nature alone – I’ll go for a six-mile hike, or dip into the woods for twenty minutes of peace. And I like to be quiet.

One of the ways I feel like I can respect wildlife while still feeling that connection is going somewhere and being still. I like the act of going without trying to pursue any specific sights. If you’re still long enough – you know, I had a white-tailed deer come up to me and it did a double take before slowly moving off. I’ve had hummingbirds study my face while I was sitting still. I try to experience, not to control the interaction.

As a kid who played in the woods and knocked over logs and stacked rocks, I struggled to move away from that at first. I was more… a consumer of the woods. It was a toy. Something I used. One thing that helped me was getting a second hand camera. I feel like my camera can let me feel that participation with wildlife in a way that isn’t intrusive or damaging. It’s a good bridge from my older ways of participating with nature to my new ways. Taking without taking.

So I focused on “Respect Wildlife” for this conversation because it wasn’t the one that came naturally to me as a child. When young, I was participating as a wild creature – digging holes, knocking things over. Now when I go, as a visitor, I’ve learned there are tons of low-impact ways we can still participate without being damaging. I witnessed the importance of this when the pandemic began. Lots of new people were visiting the quiet places I loved and they were reshaping the landscape. It was a stark example for me.

M: I’m delighted that you’re Midwest-based. Growing up I had a lot of friends that would deride our nature for other places, and I’d be angry about it. What would you say to those folks that might not feel connected to nature in their backyards, Midwest or otherwise?

Jarod: Oh boy, I went and lived in Seattle for a year. So you had the 80-foot tall Douglas fir trees, and the mountains, and the orcas not far off. When I drove back, I did it in like a single 38-hour stretch. Part of that was because, when I started to see the Midwest again, I felt like it was so beautiful and I was so excited to see a landscape that had before been sorta invisible to me. Sorta standard.

So I stepped away for just long enough to come back and think, “oh, this is gorgeous.” And it really is. The mix of tree species. The gentle hills. A kestrel on a phone line.

Going away for a year gave me a new perspective.

Sometimes the cure for that malaise we all feel seeing the same stuff everyday is to learn about it. Dig into it. I might be able to look out and name all the tree species just beyond my window, but that doesn’t mean I know them. Sometimes we take a word and use it to dismiss a whole thing or category of things. The possibility of learning something new about a familiar place, deepening your knowledge about a thing or concept, can fundamentally change and enrich your experience.

And, also, I think we get too caught up in the branding/marketing aspect of “well, what is real nature and what isn’t?” If there’s a tree you can touch on the sidewalk on your way to work – touch it! It’s right there, nature. That one tree is alive and rich with complexity and history. Get to know it. A tree by a sidewalk. A spiderweb on your front porch. Moss on a brick wall. Ask questions about these things.

It doesn’t matter where it is – this is about noticing, often, rather than going out in pursuit of “real nature.” There is magical nature near you, and you can find it by stopping, staying still, and noticing. We can all reexamine what we consider “common.”

M: I like to end these interviews with the same question for everyone. If you had to boil down all of your life lessons and experiences into one sentence to share with the world, what would you say?

Jarod: I wrote one ahead of time because I’m a poet and I had to [laughs]. As context, I spent a lot of time trying to not feel my feelings in a lot of different ways. I didn’t want to try too hard on account of the possibility of being shamed or feeling like a failure. This was true for me in school, in relationships, and in my mental health struggles. A big life lesson I’ve had so far is to stop that.

So my sentence is “to feel deeply is dangerous, but to do anything else is a tragedy.”

Let’s protect and enjoy our natural world together

Get the latest in Leave No Trace eNews in your inbox so you can stay informed and involved.