Research & Education

A Red-Tailed Hawk’s Rehabilitation and Release: Emily Davenport’s Story

In March of this year, I received a phone call from my wife’s coworker. A relative amateur to the world of animal husbandry, she’d come home to find her beloved pet duck out in the yard… sans its head. She was unsure what to do as the perpetrator remained on her premises despite attempts to scare it away.

As a former raptor biologist and forever raptor enthusiast, I ended up being her first dial. In an academic past, I’ve had to be inventive in capturing hawks – using centuries-old falconry techniques like dho gazas and bal-chatri traps to capture them. This juvenile red-tailed hawk, though?

We caught him with nothing more than a little patience and a mesh wire bucket – and that was the indicator that something was wrong with this bird. A few phone calls later, we got in touch with the hero of this bird’s story, Emily Davenport. Emily serves as the Founder, Executive Director, and Certified Wildlife Rehabilitator for Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance and nursed him back to health.

I met with Emily this week for the release of the hawk, as well as for a short interview about her work, what it means to work in raptor rehabilitation, and how Leave No Trace principles can help the public better support our avian friends. Special thanks goes to Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance, Nature’s Educators, Critter Care Animal Hospital, and the other nature-based organizations who contributed to this work.

M: Hi Emily! Wonderful to see you again. And wonderful to see you looking well, red-tail. Emily, could you walk us through what may have happened to him, before he entered our lives and ended up in your care?

Emily: First off, it is worth mentioning that less than 25% of birds of prey make it to their first birthday – it’s a tough life out there. From his markings, we can tell for sure this is an immature red-tail. As these guys learn to hunt and maneuver their landscape, they go for broke and hit their prey hard – or sometimes, as they’re learning, they perch and land too hard.

When we received him, the second digit on his left foot was very swollen – after some diagnostics, which we’ll talk through in a bit, it became apparent that this swelling was consistent with a broken talon.

More than likely through hunting, or landing, or perching… somehow he broke that talon off digit two, bacteria invaded the wound, and as it sealed up a bad infection took root. When you’re out there in the wild, there’s no antibiotics or anything, so it was going to invade the rest of him in time.

He was slowly declining, as you witnessed. That slow decline is why, I think, he was looking for those easy food sources in backyards in Denver.

M: So, once he was in your care, check-up and treatment consisted of what, exactly? What does it look like when a bird like this one ends up in a raptor rehab facility?

Emily: The first and most important thing we do for wildlife patients is supportive care. For this bird in particular – we could see his injured toe, but he also just seemed off and we weren’t exactly sure why. He was acting quite dull and it is up to us to determine why that is.

He had a much thinner body weight than what we would consider healthy. He wasn’t emaciated, but was thinner than we wanted. The first 24-48 hours for him were hugely important from the supportive care aspect.

We did an evaluation, a quick but thorough one – we try to be as hands-off as possible with raptors since they can be very stress-prone. This consisted of making sure there was no head trauma, no broken wings, no eye injuries, no issues with the mouth… Once we were able to realize it was really just the toe, the next step began.

We gave him some thermoregulation to warm up his body temperature. Low body temperatures can be dangerous, especially if you’re giving the animal food, water, or medicine. He was given his own space in a crate to help him calm down while we administered subcutaneous fluids – refilling him with electrolytes. Then we gave him anti-inflammatories to alleviate pain and swelling in that toe.

Depending on the patient, rehabilitation can look a whole bunch of different ways. Regardless, though, those first 24-48 hours have a high focus on supportive care, triage, and then working with our veterinary partners to diagnose what is going on.

He was a bit of an abnormal case from what we see, honestly.

M: Oh, really? How so – what are most cases you see?

Emily: Well, here in Colorado we’ve done internal studies and found that 95% of all animals that come into our wildlife rehabilitation center come in due to anthropogenic causes. Anthropogenic meaning that they are human-caused.

These can be accidental in nature – events such as a bird colliding with a window, or being hit by a car, or ingesting rodenticide – but, sadly, they are also sometimes brought in due to intentional harm by humans. Most often this is due to someone finding a bird that had been wounded by gunfire, despite hawks and birds of prey being protected under the Migratory Bird Act.

There are three main types of arrivals we receive – the top being collision cases of some nature, followed by orphaned animals, and finally dog and cat attacks. Over 30% of all cases we see are collision-based.

M: I can’t imagine seeing too many hawks attacked by dogs and cats – would you mind sharing what other kinds of animals you get in your care? What are you licensed to do?

Emily: Oh yes, it is mostly small mammals and songbirds we care for in relation to dog and cat attacks.

Here at the Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance we are licensed to handle many kinds of wildlife, not just raptors. I’ve been working with wildlife for the last 12 years, and have been a veterinary professional for almost 20 years now (wow, terrifying to say that out loud!).

If you’re going to take an animal to a rehab facility, make sure they are licensed specifically for your animal. I hold a license for all migratory birds, including raptors, and then I also hold a license for small and medium mammals up to the size of bobcats.

My specialization, though, is raptors – that’s my go-to, where my knowledge is. I’ve worked with raptors as small as flammulated owls all the way up to California condors. In fact, if raptors are my specialty, vultures and other scavengers could be viewed as the specialty of my specialty.

M: Thanks for that clarification. Back to our red-tailed hawk friend – so after those 24-48 hours of supportive care, what are the next steps in diagnostics?

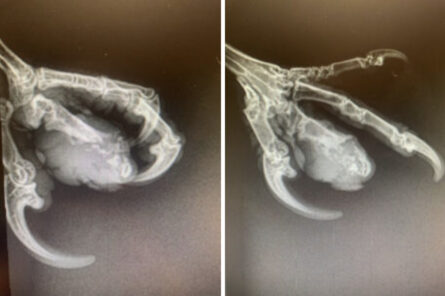

Emily: Yes, so we worked with our veterinary partners to find out what was going on. We knew from initial evaluations he had the swollen toe, but we were not sure if it was due to a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection. There was also a concern that it might be a cancerous growth in nature. Quite a bit of diagnostics were necessary – a lot of things had to be ruled out before we could treat him.

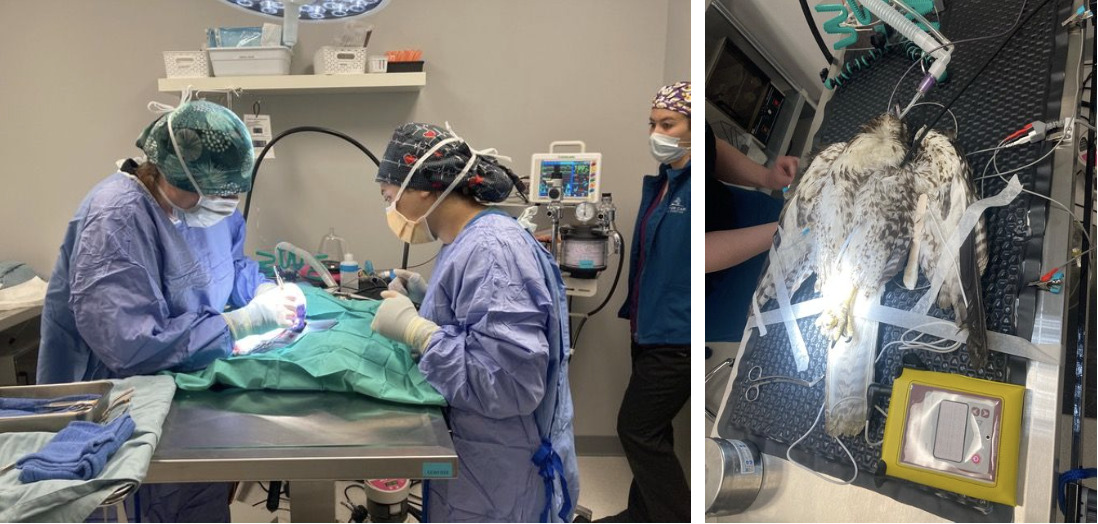

Not only did we take radiographs, we also did a test called a Fine Needle Aspirate. A little needle goes into the skin of the tissue that is infected, then we put all those cells on a slide under a microscope.

On that Fine Needle Aspirate, we were able to determine that there were no cancerous cells, but there were significant inflammatory cells and significant bacterial cells.

This is what allowed us to make the diagnosis of a likely broken talon, of sealed-in bacteria. He was officially diagnosed with osteomyelitis – a fancy term basically meaning bone infection. He had such a severe infection that it actually infiltrated and was eating away at the bone.

We put him on heavy-duty antibiotics for 4-6 weeks. The first two weeks, it wasn’t working at all – in fact, the infection was growing. We switched to another antibiotic, one focused on bone infections, and that began to work better.

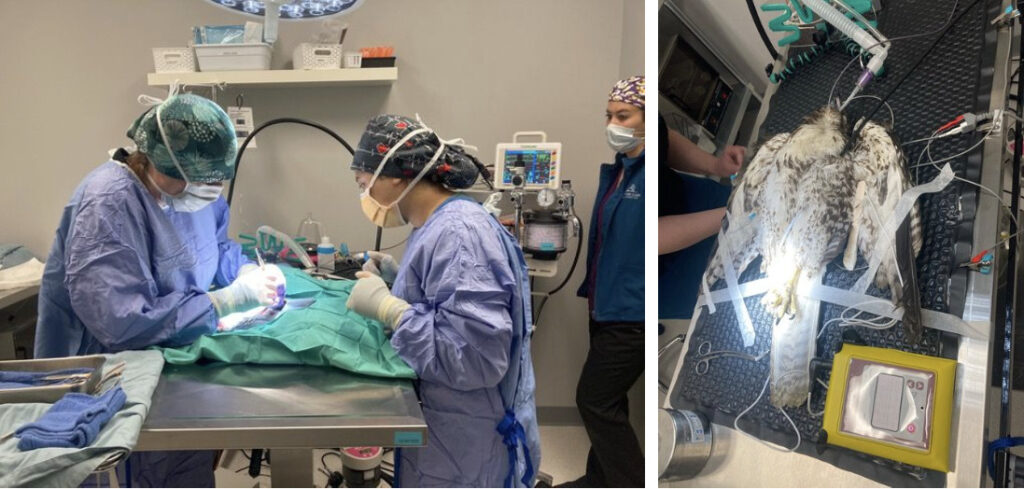

At the end of the six-week period, he was still not healed. It was still swollen and so, while it is basically always our last choice of options, we ended up deciding that amputation of that toe was necessary. We worked with our veterinary partners at Critter Care Animal Hospital – who are all absolutely amazing and all possess wildlife rehabilitation backgrounds.

They did the surgery, which was very successful, and then we kept him on antibiotics for another month, making sure the bone infection wasn’t going to migrate to other tissues.

M: In all, he was in your facilities for about three months before this week’s release. What kind of checks must a bird pass through before it can be designated as fit to release, beyond a lack of infection?

Emily: Such an important question, because he was a unique case. Generally, I am against releasing any bird back into the wild that has undergone any kind of amputation. We were incredibly observant of his feet and ended up having multiple veterinarians and biologists agree with the assessment that he was fit for release back in the wild.

As for all the hurdles he had to clear… First and foremost we had to make sure we could get him back up to an appropriate fitness – appropriate body weight, appropriate muscle mass, and appropriate cognitive function. He was back up in just a few weeks. Then there were the weekly checks of questions including:

- Does he maintain his body weight?

- How are his feet healing?

- Has his infection come back?

- Is he able to stand and perch normally?

- Does he get any kind of sores or pain from missing that digit?

- Can he hunt and kill successfully?

Luckily for him, he made it through his entire course of antibiotics with no sign of infection elsewhere. We looked at his feet for signs of sores or abrasions, pink or irritated tissue… If a bird has a deficit on one foot, they can sometimes get pressure sores on the supposed “good foot.” Luckily for this red-tail, we didn’t see any of that. He was using both feet normally – it helps that the missing digit was not the hallux (think velociraptor claw in the first Jurassic Park).

Next, of course, was “can he kill?” Raptors hunt and kill with their feet – they’re meateaters. We ethically can’t release a bird of prey that has a deficit unless we are able to confirm that they are able to hunt and kill.

Live mice were first – he was very efficient. Next came small rats – he was still efficiently able to kill these smaller rodents. Last test – an adult jumbo male rat, whom he killed with both feet. That was the day I knew that he was going to be 100% releasable.

M: Obviously, we don’t want everyone going out and picking up hawks. What should people do when they see a bird that looks injured on their property, hit a window, or when out in the field?

Emily: This is a really important question for the public – we heavily rely on the public to get birds to us.

First, please note that not all birds we find on the ground need our help. So if there is nothing obviously wrong with the bird, don’t pick it up.

However, if one is obviously bleeding, or has a wing at a strange angle, or is dragging a bad leg, or if you’re just unsure and think they could be injured… Contact your local licensed wildlife rehabilitator and ask for direction.

Most will ask for a simple cell phone picture. They can determine if it should be left alone or if it needs immediate help. And, if it does need help, the best thing to do is place it in a cardboard box with ventilation holes in it for transport.

I tell the public who might be nervous to capture a large bird to treat the bird like a giant spider – put a cardboard box over the top, then slide something underneath it. Lo and behold you have it ready to transport without touching it! There’s lots of different ways to go about it.

Regardless, the first step in these situations is to contact your local licensed wildlife rehabilitator. Licensed rehabilitators will hold licenses through their state, and for birds they will also need US Fish and Wildlife Service licensing.

M: From the organizational side, I know some of Leave No Trace’s Gold Standard Site partners close off trails close to breeding raptors. What about individuals? What does the Leave No Trace principle “Respect Wildlife” look like when concerning raptors?

Emily: This is so important with raptors – there’s such awe and majesty tied to them. Eagles, hawks, falcons, owls, vultures – respecting these raptors is important for many reasons.

A study was done a few years ago that found, worldwide, 52% of raptor populations are in decline… and 90% of all vulture populations are in decline. One of the things we can do to be good stewards is to respect them.

Sometimes raptors are villainized for eating meat – some people get mad when a Cooper’s hawk is picking off songbirds from their bird feeder.

Some basic things? We can put up nest boxes and plant native plants to give them a better microhabitat, promoting coexistence. We can let them be when they’re nesting and respect their space, not disturbing them.

We can keep our cats indoors and our dogs on leashes, so that cats don’t kill some of our smaller raptor species. And, as your friend experienced, we can keep our backyard chickens and ducks in areas that are protected with overhead cover.

M: She’s built that enclosure, don’t worry! I know that your organization, the Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance, has an exciting summer ahead of itself. What details would you like the public to know about your organization?

Emily: The Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance was founded back in 2017. We really like to say that our vision is to “elevate the care and protection of wildlife” and we do that by fostering a sense of community and collaboration with the public.

We like to say we’re for people, we’re for professionals, and we’re for wildlife.

For people, we focus on educational outreach – going out into the public, setting up booths, setting up human-conflict resolution cases. In those we talk about managing our environment, our communities, things aligned with Leave No Trace values.

For professionals, we host an annual wildlife conference for wildlife professionals where they get continuing education credit and knowledge. There’s few spaces nationwide where wildlife rehabilitators can get this continuing education, so we’re excited to take this on.

Lastly, of course, we take care of wildlife through our wildlife hospital and rehabilitation center. Our goal is to take in those injured, orphaned, and ill wild animals with the goal of releasing healthy members of the breeding population back into the wild.

Most exciting this summer, for us, is that we finally have a forever home in Sedalia, Colorado. We really hope to grow into it over the next six months… we’ll start with raptors and songbirds, with the goal to expand to waterfowl and small mammals as well. Exciting!

M: And, broader than just your organization, is there anything else you wished folks knew about wildlife rehabilitation work?

Emily: It is more of a professional industry than most people realize.

However, a lot of people don’t realize that wildlife rehabilitation is still a fledgling field. It’s only been around for one generation before mine. So we are moving at hyperspeed in the wildlife rehabilitation field.

My generation is now incorporating real medicine, better scientific research, and better understanding. We’re really helping to propel the field forward professionally.

Many folks don’t realize that wildlife rehabilitation is the professional care of sick, orphaned, and injured wildlife. We work very closely with biologists, with scientists, with researchers, with veterinarians, and with our regulatory agencies – all to ensure that the wildlife we are taking in can be responsibly and ethically treated and rehabilitated so that the individuals we release back into the wild are healthy members who can be a part of the breeding population.

I like to take the ecosystem approach, sometimes called a one-health approach, to wildlife rehab – we focus on the individual at hand, and then also the population as a whole, the ecosystem as a whole, and our overall community as a whole.

As we talked about, the majority of individuals that come in do so due to human causes – so wildlife rehabilitation is an important way to fight back some of these negative anthropogenic effects.

When it is human-caused, it’s not really “letting nature take its course,” is it?

Wildlife rehabilitators have been instrumental in helping to save endangered species. Rehab practices have been used to save the California condor, the black-footed ferret, the bald eagle, the peregrine falcon, the boreal toad… just to name a few.

We are also instrumental in identifying diseases on the landscape. Since we’re on the frontlines, we often see diseases before the scientific community does, as well as being able to identify pollution areas.

M: Okay, it’s release time, time to wrap up. Last question is the same for everyone – if you had to boil down your life lessons into one sentence for others, what would you say?

Emily: I’ll tie it back to our red-tail. I had a professor once tell me “humans have a tendency to worry about the past and dwell on the future, so we’re not in the present – why not be more like a red-tailed hawk and just survive the day?” I love that – be like the red-tailed hawk and just survive the day.

_______________________

Editor’s Note: Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance had a partnership/merger with Nature’s Educators, another wildlife centered Non-Profit Organization, from mid 2019 until mid 2022, overlapping with this bird’s care. Nature’s Educators had acquired this facility in Sedalia, Colorado and rehabbed the building in order for it to be suitable for wildlife usage. Nature’s Educators is a 501c3 non-profit organization with a mission to inspire individuals to understand, respect and conserve wildlife through educational programming & experiences.

Devin Jaffe, Director of Nature’s Educators, went into this partnership/merger with Rocky Mountain Wildlife Alliance to balance out wildlife rehabilitation with wildlife education. As people may, or may not, know, rehabilitation of wildlife is a very costly endeavor when it’s done right, but is always worth it at the end of the day when animals, such as this red-tailed hawk, are able to be released back into the wild.

Nature’s Educators is now located at 4498 BearPaw Avenue, in Florence, Colorado, at their new Nature Center. They recently acquired a 9 acre property next-door to this facility for those looking for further in-person raptor and wildlife education. For more information please visit their website at www.natureseducators.org.

Related Blog Posts

Let’s protect and enjoy our natural world together

Get the latest in Leave No Trace eNews in your inbox so you can stay informed and involved.